"Sharing a quite balanced article out of China"Sharing a quite balanced article out of China that a couple of the lads here tracked down .....

Manono锂矿洗牌,紫金矿业获权益再平衡 行走的石头 2023-10-24 $紫金矿业(SH601899)$ 昨日发布晚间公告,公司受邀主导世界级锂矿Manono... - 雪球

行走的石头 2023-10-24 $紫金矿业(SH601899)$ 昨日发布晚间公告,公司受邀主导世界级锂矿Manono东北部项目勘探开发。据了解,Manono锂矿PR13359探矿权已归还并登记至Cominiere(刚果矿业开发股份有限公司)名下。根据紫金与Cominiere合资协议,双方通过曼诺诺锂业持有该探矿权东北部分项目(...xueqiu.com

Published on 2023-10-25 14:19from snowball · Jiangsu

Follow _

Manono lithium mine shuffle,Zijin Mining receives equity rebalancing

Walking Stone2023-10-24

$Zijin Mining (SH601899)$ issued an evening announcement yesterday,The company was invited to lead the exploration and development of the world-class lithium mine Manono Northeast Project.It is understood,Manono lithium mine PR13359 exploration rights have been returned and registered to Cominiere(Congo Mining Development Corporation)under one's name.According to the joint venture agreement between Zijin and Cominiere,The two parties hold the northeast part of the exploration right through Manono Lithium.(Exploration Rights No. PR15775),Among them, Zijin Mining holds 61% of the equity of the joint venture.,Cominiere holds 39% interest.

It was noted that Zijin Mining, which has always been strict in information disclosure, used the following words in its announcement:"Northeast part of the mining rights project",rather than the Northeast"A certain project".alert immediately,Mining rights were split!Some friends in the industry asked about this on WeChat,I took some time out from my busy schedule to type out a few paragraphs of text..

1-Significant reshuffle and division of mining rights.The original PR13359 was split into two,Cominiere acquires flagship resource area,Zijin obtains the best prospect exploration area in Northeast China.

The original outer exploration rights of Manono’s northeast extension and southwest extension were randomly cut up.,Congolese environmental and mining consultancy to divide outer extension;AVZ only retains the external extensions after castration,And its mineral rights are surrounded by exploration blocks of the Congolese Environmental and Mining Consulting Company.

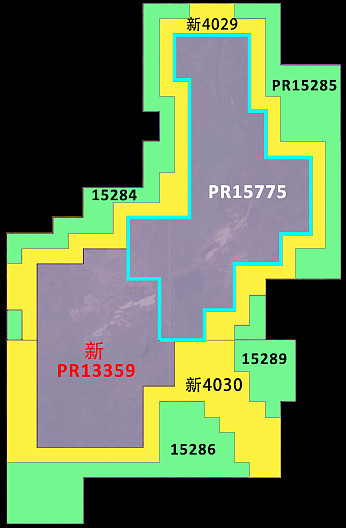

The two pictures above reflect the aftermath of the Manono incident,The mysterious operation of mineral rights changes in core areas.The original PR13359 was split into new PR13359 and PR15775,The former is owned by Cominiere,The latter is controlled and dominated by Zijin Mining through cooperative companies.The original peripheral PR4029 and PR4030 were cannibalized and divided.,AVZ currently holds only the yellow area in the picture above,Congolese environmental and mining consultancy holds green zone.

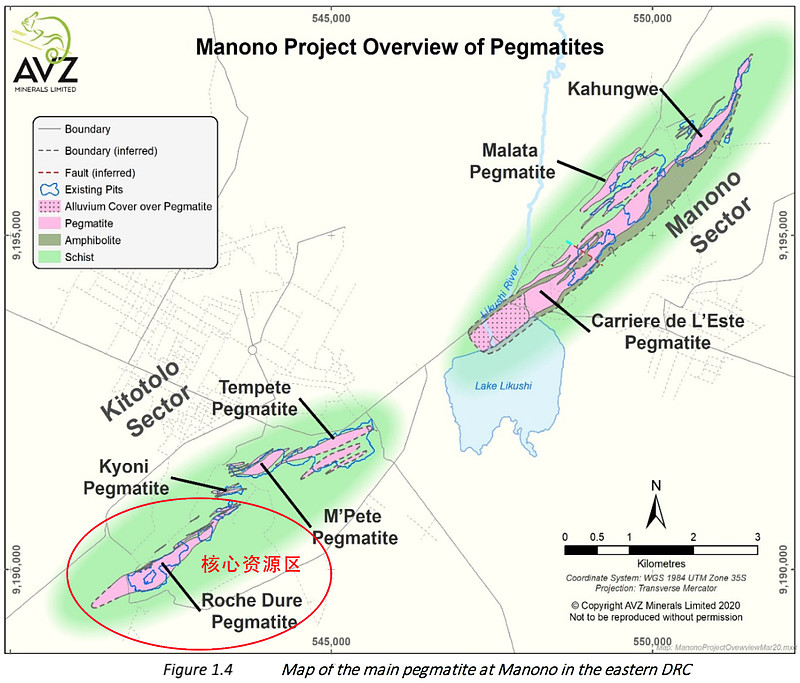

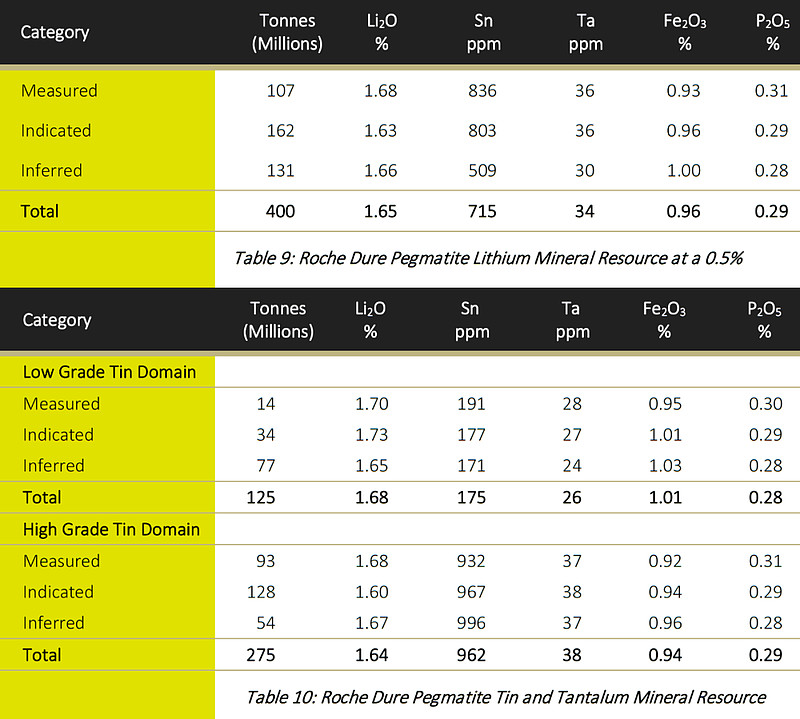

2- The flagship mining right PR13359 was taken back by the government,The discovered core lithium resources are fully controlled by Cominiere.Although the project is called Manono,However, the resources discovered by AVZ exploration are actually in the Kitotolo Pegmatite Belt.,rather than the Manono pegmatite belt.Areas where AVZ has carried out extensive exploration discoveries and submitted resource estimates in the past,Strictly limited to the lower left corner of the picture below,That is, in the Roche Dure pegmatite in the southwest area,The resource estimation results are shown in the table below.

3- PR15775 controlled by Zijin Mining does not include proven high-grade lithium ore resources,However, the exposed Manono pegmatite zone,In addition, AVZ’s past exploration has already discovered mineralization through drilling.,Exploration prospects are very good.

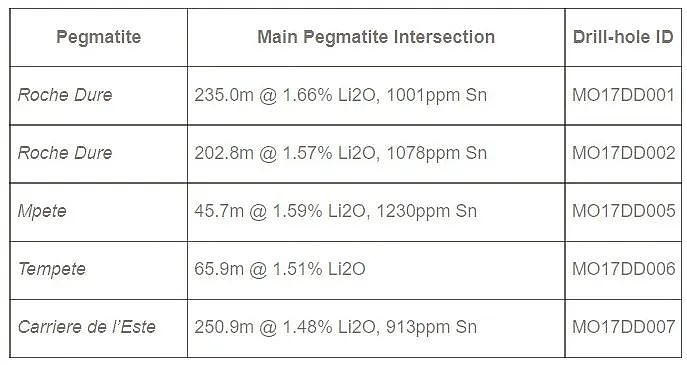

According to AVZ official website information,The MO17DD007 borehole constructed as early as 2017 discovered ore thickness of up to 251 meters in the Carriere de I'Este pegmatite in the Manono pegmatite belt.,Li2O grade is as high as 1.48%,Mineralization at 913 ppm tin grade.

3- Zijin Mining’s previous deal to purchase 15% of Dathcom’s shares was completed"reconciliation",The acquisition price of US$33.44 million was directly used to obtain 61% of the equity consideration of the PR15775 exploration rights project company..Zijin Mining becomes one of the foreign-funded enterprises that invested in the original Manono project,So far the only company that has received equity rebalancing.

4-Commentary and analysis of future trends of the Manono lithium mine incident:

Zijin Mining has occupied the mining news attention of Chinese people for nearly two months.,First, PNG’s Porgera gold mine won new mining rights,Then the investment in the Manono lithium mine project was rebalanced and equity repaid,Demonstrate the ability of large international mining companies to respond to and resolve national risks.

This operation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo government is quite outrageous.,Obviously there is someone behind the scenes to help;Both sides,Can advance or retreat!

Government-related transfer of 15% stake in Zijin Mining received amicable settlement and equity rebalancing payment.The core lithium ore resources discovered by the original AVZ are classified into the new PR13559 and are controlled by Cominiere,Not moving for now.One side can still continue negotiations with the Australian government or AVZ listed companies with strong international influence,On the one hand, we can still wait quietly for the outcome of the international arbitration in Paris..after all,Under strong diplomatic pressure from the Five Eyes alliance countries,The Congolese government will not make any rash decisions in the short term..This leaves a way for AVZ to regain the Roche Dure core mineral resources of the Manono project in some way in the future..

Due to settlement and equity rebalancing,Zijin Mining seems to have temporarily withdrawn from investment in the core Roche Dure lithium mine.,Of course, we do not rule out seeking investment in the future..But to some extent,Zijin Mining currently occupies a favorable track.Obtain very favorable prospecting rights,And won the development rights of hydropower stations in the region,The highway to Manono is also advancing.Zijin Mining is racing against time,If PR15775 obtains exploration findings as soon as possible,and build the mine quickly,In the future, obtaining the development rights of the core resources in the new PR13559 will occupy the first-mover advantage..

AVZ is under great pressure now!From a legal perspective,The current embarrassing situation is that the mining rights of the projects that were originally controlled have been divided and divided, leaving only the useless narrow corridor of the second ring road.,and surrounded by three peripheral rings controlled by Congolese Environmental and Mining Consulting Company.Faced with capital market shareholders again"Inadequate, timely and transparent disclosure"Waiting for prosecution.same,Today’s ASX disclosure still did not mention the latest mineral rights split and split..

The future of the Manono lithium mine remains unclear.Reconciliation of the dispute over the transfer of 15% equity of the original project company,Removes obstacles for AVZ to assert reasonable expectations of its future 66% stake.Have a premonition,The Congolese government is eager to seek political and economic support from the West,At the same time, due to political pressure from the United States and other Western countries,,It is likely that the new PR13559 will eventually be subjected to a series of harsh conditions"transfer"at AVZ.Sure enough,Zijin Mining is likely to be able to protect its interests in it

I am assuming you are being facetious......