Zijin’s poisoned legacy

A toxic spill last year blackened the name of Chinese metals giant Zijin Mining. But, in Fujian, its broken promises and environmental failures have a longer history, writes Yang Chuanmin, joint winner of the in-depth reporting category at the 2011 China Environmental Press Awards.

Yang Chuanmin

April 13, 2011

A serious pollution incident at a Zijin Mining copper mine in July 2010, sent shockwaves across China. Forty days later, Southern Metropolis Daily

reporter Yang Chuanmin travelled to Fujian province to investigate the local impact of the company’s operations. There, she found a legacy of ill-health, polluted land and broken promises. This report is the joint winner of the in-depth reporting category at the China Environmental Press Awards, 2011, run by chinadialogue

and The Guardian

.

Even on the hottest summer days, few women wear skirts in Bitian village. They do not want to expose their feet, which are covered with festering blisters from the water of the Ting River.

The pollution disaster here, in Fujian province, eastern China, has brought Zijin Mountain into the public eye. Before July, 2010, the metals giant that runs the pits here – Zijin Mining – was upheld as an example of “double excellence”: bringing both economic benefit and environmental protection.

Bitian has not had usable water for a long time. According to statistics from the village authorities, more than 200 of the 305 families here have to walk down a very long road every day to collect mountain water. One villager, Zhong Sanlian, allowed me to see her sore-covered feet. After she washes her clothes in the river water, she said, her feet swell up for several days and itch painfully.

The village secretary, Huang Jingxin, said: “Your hands start to itch as soon as you come into contact with the river water.” Even the colour of the Ting River scares them. When there is no wind or rain the water is green. But when it rains heavily, sediment from the bottom of the river is brought up and the water turns into a rusty sunset colour.

Losses to the downstream fishing industry have already been calculated. However, damage caused in the immediate area as a result of July’s disaster has not yet been evaluated.

The villagers said that all the fish in the river have been killed off. River life has always been a source of pride for the people here. Turtles used to sell for more than 70 yuan (US$10.7) per jin (around half a kilo). They also used to catch grouper, beard fish and eels, which had sweet and tender meat, like tofu. July was the last time anyone here caught a fish more than half a metre in length. That fish died quickly and a group of the villagers bravely ate it together. Among them was 30 year-old Bi Bosheng, who works at the neighbouring Wuping Zijin mine, in a shaft over 400 metres deep. He has a different take on life and death to most: more and more people dare not eat anything from the river. Another villager, Huang Lihua, suspects it is as dangerous as taking poison.

Even now, Bitian has not posted a report on local water quality. It’s as if the pollution incident had nothing to do with this village. Nobody has raised the issue of compensation or how to deal with drinking-water problems. The only comment has come from the Dahang County TV station, which has been broadcasting daily since the beginning of August that Ting River water is meeting quality standards on every count.

Local people are too scared to eat the fish here, but the results of official laboratory tests have “confirmed” that Ting River water is meeting standards. The results were posted on a bulletin board on Jiangbin Road in Shanghang County.

According to inside sources, the former head of Shanghang County Environmental Protection Bureau has been removed from office. The new head, Li Yongtao, goes to Zijin Mountain for monitoring purposes every day. La Jilong, the head of the environmental monitoring station in Yongding County, which is situated downstream of Shanghang County, even told me that “already there are no traces of copper ions”.

This does not calm the fears of the locals, however. Exasperated, village head Zhong Wenfang said: “At present we don’t know what to believe – whether the problem has been resolved or not.”

Shadow of cancer

The villagers here have long mistrusted the authorities. At the end of June and beginning of July, the river at the foot of Bitian village turned strange shades of blue and green, like synthetic colours in an oil painting. Every day, the villagers see the environment inspection vehicle come to the bridge at the entrance to the village to take water samples. They know something is wrong, but up until now nobody has explained to them what has happened.

According to China’s “Environmental Protection Law”, if there is a sudden incident in a company or government unit that could cause an environmental accident, then “the people who may come to harm as a result of the pollution must be informed in a timely fashion”. Zijin Mining clearly failed to comply with this.

The distrust goes further back than July, however. Villager Huang Lihua has not dared to drink the river water for several years. He has used several hundred metres of rubber tubing to divert mountain spring water from the other side of the mountain to his home. Three or four years ago, his cattle, which would frequently go down to theriver to drink, became ill and died. He buried the cattle. He did not dare to eat or sell it.

Even without the impacts of July’s accident, Bitian is paying a price for the mining operations on Zijin Mountain. The mountain lies to the north-east of the village. When it is windy, ore residue fills the air. On bad days, even the houses on Zijin Mountain are hard to see. Since the beginning of this century, when the peak of Zijin Mountain was blasted for mining, the environment of Bitian village has steadily deteriorated.

Last year, Zijin Mining gave Bitian village a subsidy to establish a running water supply. However, this year water samples from the village were sent for laboratory testing and the water quality found to be sub-standard. The villagers said they now use it to flush their toilets. Huang Lihua said: “The water from the Ting River used to be delicious, but now we don’t dare to drink it”. Villagers with enough money buy clean drinking water like city people.

What really frustrates the people of Bitian is that, apart from the pollution, Zijin Mining hasn’t brought them anything: there have been no benefits for the villagers and gaining work at the company is not an easy task.

This cannot be counted as a poor village. At the beginning of the 1990s, many people bought shares in Zijin Mining and made some money. But those with funds have moved away. Zhong Wenfang, the village head, said that the people still there are those with no alternative.

Most of the older Bitian villagers know Zijin Mining’s chairman, Chen Jinghe, who as a young man used to climb Zijin Mountain in the day and, in the evening, eat his dinner at the Bitian village hall. And so, for the past two months, a group of village bigwigs have been going to Zijin’s offices to try to speak with Chen. Zijin Mining has, in response, promised to resolve their drinking water problems, but still nothing has been done.

The relationship between Zijin Mining and the Shanghang county government is set out in the company prospectus. In the last restructuring, Zijin Mining changed froma state-owned enterprise to a modern shareholder-owned enterprise. However, the largest shareholder is still the Shanghang county government. Many government officials have positions in Zijin Mining and these posts have been disclosed to the media.

There are pressures from both above and below. Zhong Wenfang said that he finds being a village cadre is too difficult: “Every day, villagers express their opinions to the village committee, saying, ‘The air is so terrible! You need to resolvethe drinking water issue!’”

The Ting River was originally the life-source of the Hakka people. Now, it has become a burden. Downstream from Bitian, Jiantou village stretches for three kilometres. Here, each household has a well by the river to draw water. The wells are all 20 to 30 years old, but have been abandoned in the last few years – nobody dares to drink the water now.

Ten days ago, another esophageal cancer patient from Bitian died. According to local medical statistics, of 40 people to contract cancer in the village in the past 10 years, 35 have died. Most of them lived in the village closest to Zijin Mountain. The village secretary Huang Jingxin told me that these statistics are “very accurate” and that most of those who died suffered from esophageal cancer, lung cancer and stomach cancer.

Many of them went to Beijing and Shanghai for treatment, plunging their families into debt. Ten years ago, there were almost no cancer patients in the village.

The Ministry of Health has not published the rate of cancer in China. However, according to statistics produced at the fifth China Oncology conference in 2008, over the past 20 years China’s cancer rate has been between 1% and 1.5%. The cancer rate in Bitian village is three times higher than this and, in the village closest to the mine, it is almost 10 times higher. The villagers say that, before mining started here, cancer was very rare, but since the mining began “most of the deaths have been caused by cancer”.

Evolution of a crisis

The environmental deterioration of the Ting River basin, which stretches from Zijin Mountain to the Mianhuatan River, has not happened overnight. And alongside this gradual process, mining expansion has continued at an alarming rate.

The Zijin Mountain goldmine started operating in 1993, kick starting the area’s industrial development. By 2000, full-scale open pit mining was under way. The Zijin Mountain peak was leveled and turned into a natural workshop for heap leaching and hydrometallurgy. Before this, open-air heap leaching had rarely been practised in southern China. In various interviews, Zijin chairman Chen Jinghe rejected the viewof industry experts that “the south is too humid and rainy for heap leaching and the situation of Zijin Mountain does not lend itself well to this mining process.”

The rapid rise of Zijin Mining is proof of the potential for mining low-grade ore. Once, the Zijin gold mine was considered a hard and “tasteless” nut. In normal circumstances, one tonne of ore would need to contain three grams or more of gold before being considered for industrial ore mining. However, most of the ore from Zijin’s mine contains less than one gram of gold per tonne, making low-cost heap leaching a good solution.

Today Zijin Mining’s vice-president, Liu Rongchun was manager of mine technology when the company was founded in 1993. In interview with

Southern Metropolis Daily, he said that heap leaching in southern China was absolutely doable as long as you choose an appropriate site and protect against waste-water seepage. He said Zijin was using the process to turn something small into something great, and that environmental protection was at the heart of the company’s ethos.

Why is environmental protection management so important in heap leaching, even though the process uses known materials?

First, an important material used in heap leaching is sodium cyanide, which is a highly toxic substance. Second, it produces a huge amount of waste: one tonne of ore could contain as little as one gram of usable metal. Handling the waste is more challenging than the core extraction process.

In 2006,

Mining Technology magazine published the article “Zijin mining: exploitation of low-grade and refractory metallurgical mineral resources”, the result of a collaboration between Changchun Gold Research Institute and researchers from Zijin Mining. It mentions that, “Heap leaching of gold is a simple, low-cost method that uses limited mineral processing equipment. Only these methods of mineral processing, namely open-pit mining and carbon in heap leaching methods + (fine orecyanide carbon) are capable of expanding production capacity, reducing operating costs and increasing dressing and smelting recovery rates, in order to expand gold production, increase enterprise profits, lower tailing grades and selected ore grades.”

Heap leaching resolves the cost issues associated with low-grade mineral mining. Figures show a linear increase in the estimated gold deposit volume in Zijin Mountain over the last 10 years. From an initial 10 kilograms, the figure had risen to 11.5 tonnes by 2006, a one thousand-fold increase. In close to two years, Zijin Mountain produced around 80 tonnes of gold, making it China’s largest gold mine.

The advent of open-air heap leaching allowed production capacity to expand. Meanwhile, the situation in Bitian village gets worse year by year. The village head, Zhong Wenfang said: “I used to think the Ting River was really wide, I never dreamed of ever expanding mines”.

Leaks in leaching

The wet copper smelter that caused July’s pollution leak employed the same principles as heap leaching. The copper is located below the layer of gold. Only in the last couple of years has Zijin started to extract it.

This wet smelting technology, jointly developed by Zijin Mining and the Beijing General Research Institute for Metals, was given an award by the China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association and the Gold Association. A researcher from the institute told me that wet copper smelting is a mature technology internationally and the greatest advantage is that you can use low-grade copper. Zijin Mountain is also the first large-scale mine in China to use hydrometallurgy to mine ore. Vice-president Liu Rongchun said this technology has been researched for 10 years and practiced for five. Twenty percent of the world’s copper is produced using bio-hydrometallurgical processes, which can raise the rate of resource utilisation.

In fact, if we look to the past, it is a miracle that Zijin Mountain copper is used at all. According to data provided by Zijin Mining, its average copper content is 0.38 grams per tonne. That is to say, from one tonne of ore, only 0.38 grams of copper is extracted, and the remainder is considered waste.

China has large quantities of poor-quality ore. Zijin Mining provides a route to low-cost exploitation, and its industry reputation is based on the model “benefit the country, benefit the people and benefit the self”.

Previously, Zijin Mining repeatedly stated that hydrometallurgy is a closed process, and there is no possibility of waste-water containing copper efflux. However, a survey of the literature revealed that, within the hydrometallurgical process, and consideringthe particular characteristics of Zijin Mountain ore, there can also be simultaneous leaching of iron and arsenic. These heavy chemicals can accumulate in the leaching solution and reduce production efficiency. During the production process, these byproducts must be carefully managed.

Liu Rongchun has confirmed this with

Southern Metropolis Daily. He explained that the company has three safeguards to prevent leaks during the leaching process. First, it secures a mat beneath the ore stockpile during heap leaching to prevent seepage. Second, it creates seepage-collection wells, to collect any solution that may have leaked during the heap-leaching of the ore stockpile. Third, to ensure that everything is perfectly safe, the Environmental Protection Bureau of Shanghang County has installed an independent water-quality monitoring device downstream of Zijin Mining’s waste-water discharge point.

According to the Environmental Protection Bureau, the pollution accident at the beginning of July was caused by the simultaneous failure of all three safeguards.The seepage collection wells and spillways were “illegally” kept open; however the findings of the investigation did not clarify if the accident was based on subjective intent or an accident.

Liu Rongchun said: “On the macro scale, we are very good – but the problems were unexpectedly caused by small details. This is a profound lesson, reflecting failures of management.”

Bigger mine, worse pollution

Across the world, hidden behind the wealth created by the mining industry, are problems requiring attention – and those most in need are the villages closest to the mines. Unfortunately, amid China’s rapid development, these places are still neglected for various reasons.

Less than a kilometre from Zijin Mountain, in neighbouring Wuping county, is Yueyangpian village. The metals found here are mainly silver and copper, but there is also gold, lead, zinc, gallium, bismuth and sulphur – all associated with large-scale deposits of silver polymetallic ore. But the mine set up to exploit these resources has also brought environmental disaster for local residents: as the wealth from mine amasses, the state of the village gradually worsens.

This mine was first set up in the 1990s and jointly operated by Sanxin Mining and Ronghe Mining. Their activities cut off groundwater supplies and some of the village farmland could not be irrigated. A government document shows that, at the beginningof 2007, this mine in Wuping County was transferred from Ronghe Mining directly to Zijin Mining by “principle leaders of the county committee of the county governmentand under the efforts of the Land and Resources Bureau” and established as Wuping Zijin. Wuping Zijin became a subsidiary of Zijin Mining Group. According to a 2008 security bulletin published by the company, Zijin Mining owns 77.5% of Wuping Zijin. Wuping county is the second largest shareholder.

In a later, expanded version of the environmental impact assessment, the mine was described as showing poor economic returns and having safety issues, including tailings hazardous to downstream villages and the Ting River. “Therefore, the best way is for a strong enterprise to lead exploitation,” it said.

Liu Rongchun recalls that Wuping County was not completely comfortable with this mine. As a result, Zijin Mining put in place a careful management plan, improved the rate of resource utilisation and standardised safety and environmental protection features.

In the second year after the take-over, Wuping Zijin put forward plans to expand capacity to “daily processing of 2,000 tonnes of ore”. Wuping county government is the second largest shareholder in the mine. The expansion plans fell under the supervision of Wuping county deputy magistrate Wang Yunchuan. Zijin Mining completed its expansion within one year.

The environmental impact assessment conducted by the Sanming city Environmental Protection Science Research Unit indicated that the biggest source of pollution wasthe waste-water emitted from tailings, most of which ended up in the Ting River.But it was confident this problem would be dealt with: “The expansion project will impose restrictions on volume of waste-water emitted. Most people in a public survey approved of Zijin’s acquisition and expansion,” the report said.

However,

Southern Metropolis Daily’s investigations show that this was not the case. After the expansion was completed, pollution was not reduced in line with Zijin’s promises.

The new tailings storage facility for the mine in Yueyongpian has been designed to sit on a high slope, and so the water level is higher than most of the village’s buildings. Yueyongpian is made up of three administrative units, including Yueyong village.Their water source is badly polluted. Many villagers told me that the most serious groundwater pollution began the year before last, after the tailings-storage facility was expanded.

The villagers of Yueyongpian cannot drink the water from old wells, which were in use for several decades; neither can they drink the water from wells dug by individual households.

The villagers showed me a pot of boiled well water. On the side there was a thick yellow layer of dirt and it tasted salty “Before there was any mining, the water was very clear and sweet,” said one old villager, Zhou Rencheng. “Now, after one night, the water gets rusty and tastes foul.”

The farmland is also badly polluted. In the 1950s, a set of small reservoirs were set up for irrigation and the water was diverted to the rice paddies with water pipes. After the reservoirs became polluted, the earth on the fields turned black and smelly. The rice takes longer to grow and the crop is stunted. When the villagers go down to the fields, they wear rain boots. If they work barefoot, then their feet will rot.

Wuping Zijin has received little attention in comparison with Shanghang Zijin, even though they are only separated by a mountain. The villagers showed me some photographs. When the national press rushed to Shanghang county for interviews, the forked road to Wuping Zijin was blocked by a rock.

When I asked Zijin Mining about the current status of Wuping Zijin’s many metal mines, the response was: “There has been no pollution of the Ting River, or in the surrounding areas.” Vice president Liu Rongchun added: “Of course, development has an effect on its surroundings, however so far this has been within an acceptable extent.” Liu Rongchun said that each mine is assessed before acquisition.

However, this assessment is not satisfactory. In 2009, a group from Yueyongpian village formed to put forward their misgivings about the mine and representatives of Wuping County came to the village for a meeting. The village team leader and village cadres also took part.

The people all said that the water tasted bad. But the conclusion reached by the county cadres was that there was nothing wrong with the water and it was drinkable. To this day, the villagers have still not seen a public report on water-quality testing done by the Environmental Protection Bureau.

Green farms to stagnant water

Not far from the expanded mine are villagers whose existence and environment are coming under increasing pressure. At Yueyang, just a fraction of the village’s original lands are still capable of supporting a farming lifestyle.

Work in the mines is also very dangerous. Gold and silver are toxic materials. Every villager knows this. Zhou Yonghong, a 42-year old local, worked at a small, private mine nearby. One day, he lost his footing and fell into the cyanide pool. He died on his way to hospital. The mine paid out compensation.

When Zijin Mining built the tailings-storage facility at Yueyong, it attracted strong opposition from local villagers. Then they built a tailings dam for Wuping Zijin. This was the fourth time that they requisitioned land during this period and the price on offer had risen – from 12,000 yuan per

mu (around 667 square metres) to 25,000 yuan per

mu.

At that time, villager Lin Meiying still owned seven plots of land. When land for the dam was being requisitioned, the county and town sent workers to her home every day. She did not let them in.

But her brother-in-law, a teacher at a middle school in Wuping, was told he would be fired if his older brother and wife didn’t agree to sell their land and so she gave in. When she went to town to have the sale certified, she stopped to apply for work in the mine as, along with her land, she had lost her source of income. But Wuping Zijin told her that, at 44 years old, she was too old for thework.

The 100

mu of farmland here has turned into the biggest source of pollution in the village. At the entry port to the tailings-storage facility, there is a large sign saying: “Tailings storage facility, entry forbidden”.

But, in reality, the villagers have not all moved away and the tailings storage facility is already in use. Hu Biaoyang even lives within the facility’s grounds. According to company plans, his house will eventually be submerged. But Hu doesn’t have anywhere to build a new house and doesn’t want to move, and so he has made two demands: the first is that the facility will not affect his current standard of living and the second is that, once the land is requisitioned, his future living will be safeguarded.

Hu Biaoyang does not have any relatives who are teachers or civil servants and the two sides are at a stalemate. From time to time, workers come and try to persuade him to give up, saying that Wuping Zijin is a state-owned company, the backbone of Wuping and the area’s biggest taxpayer.

Hu Biaoyang has kept some pictures of the site of the tailings-storage facility before it was flooded: a green rice field in the summer and yellow withered stalks after the winter reaping. Now it is just stagnant water; even the mosquitoes avoid it. Some villagers’ graves were not moved in time and have also been submerged under the reservoir. The wells in front of the houses are gone too and the reservoir water will soon flood his house.

During my visit, the villagers looked out on this stagnant water in consternation.They still remember their feelings of reluctance about the project. They have filmed the farmland and made dvds as something to remember their home by. But they also know that, even if the water receded, the fields could not be cultivated.

Cancer patients

For fish farms downstream, pollution from mining means economic losses. For the villagers of Yueyang and Bitian, meanwhile, it is a challenge to their basic right to life.

Even small-scale mining can produce serious pollution. The people of Yueyang told me that, for half an hour every day, their village is enveloped in acrid smoke from the privately owned Jinshi mine nearby.

Ten years of mining has turned Yueyang into a “cancer village”. There are more than 3,000 people living in the three administrative villages of the Yueyang area.

In the past five years, about 60 to 70 cancer patients have died in these villages, many of them married couples or siblings. The youngest cancer patient is only 18 years old.

Southern Metropolis Daily obtained a detailed case list. The most common causes of death were stomach cancer, lung cancer, esophageal cancer and liver cancer.

Guan Yangwen and Guan Shengwen were brothers. They died in 2002 and 2006 respectively. Last year, their sister was diagnosed with leukemia.

Guan Zhongwen and Lin Jindi were a married couple. Guan died of stomach and liver cancer and Lin breast cancer. Their only child was orphaned. Zhou Renxi and Qiu Yongzhao, also a couple, were both killed by cancer.

Lin Meiying’s father, Lin Zhanqin, his sister’s parents-in-law, Zhong Xiuzi and Wen Dengchun, and his father’s older brother – all of them died of cancer.

The villagers have received no compensation: it is very difficult to prove the connection between cancer rates and environmental degradation, and difficult too to determine where the main responsibility lies, as the mine has been operated by three mining enterprises.

Twenty year-old Zhou Meifang grew up on this land. At 18, she went to medical school in the city. Last year, when she returned to Wuping for National Day, she fell ill and was diagnosed with leukemia at the local hospital, which sent her to Fuzhou for treatment. Three weeks later, she died. Her mother did everything she could, borrowing 20,000 yuan (US$3,000) from family and friends for treatment, but the doctors were unable to save her. Steeped in debt, her family faces a troubled future.

The villagers from Yueyang even envy villagers elsewhere who have lost their land. Those living under the shadow of cancer are not able to seek compensation. And, as much as they want to move away from their polluted homesteads, they have nowhere to go.

Yang Chuanmin is a reporter at Southern Metropolis Daily

, and joint winner of the in-depth reporting category at the 2011 China Environmental Press Awards.

This article was first published by Southern Metropolis Daily

on September 1, 2010.

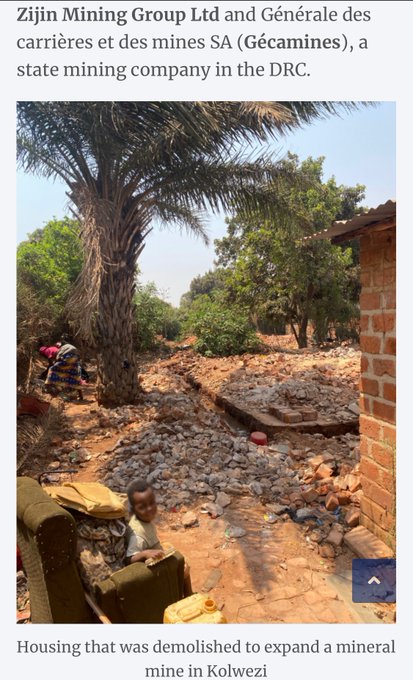

Homepage image from Southern Metropolis Daily

shows the impact of Zijin’s toxic spill in July 2010.

A toxic spill last year blackened the name of Chinese metals giant Zijin Mining. But, in Fujian, its broken promises and environmental failures have a longer history, writes Yang Chuanmin, joint winner of the in-depth reporting category at the 2011 China Environmental Press Awards.

dialogue.earth