By John Dell’Osso and Douglas Gillison If you live near buried treasure—huge deposits of oil and gas, eye-popping reserves of gold, copper, bauxite, cobalt and other things that make the world go round—odds are you’re very poor and your leaders are autocratic. Across the world, more than two...

africauncensored.online

Bribery, Brothers and a Bank

December 7, 2021

By John Dell’Osso and Douglas Gillison

If you live near buried treasure—huge deposits of oil and gas, eye-popping reserves of gold, copper, bauxite, cobalt and other things that make the world go round—odds are you’re very poor and your leaders are autocratic.

Across the world, more than two thirds of the people struggling in extreme poverty live in resource-driven economies, according to research from a decade ago.

Your leaders will likely help themselves to the nation’s wealth but cut spending on education while boosting military funding, for example.

In the extreme, according to the author Tom Burgis, the social contract breaks down “because the ruling class does not need to tax the people to fund the government—so it has no need of their consent.” This is by now a familiar tale.

But this month, The Sentry, a team of investigators committed to fighting kleptocracy and ending violence by exposing grand corruption and pushing for reform, exposed a painful new chapter in the story.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, perhaps the resource state par excellence, former president Joseph Kabila sold his people the vision of a bright future in which they would trade millions of tons of ore to buy about $3 billion in gleaming new Chinese-built roads, hospitals and universities, helping the country to emerge from decades of war, corruption, and plunder.

Sadly, Kabila also saw this as an opportunity to take a very large cut for himself by leveraging the project to steer tens of millions of dollars in bribes from gigantic Chinese construction companies into his own pocket.

You can read this in our new report entitled “The Backchannel,” part of a broader leak project called Congo Hold-up, which saw media outlets and non-profit organizations representing over a dozen countries spanning four continents make sense of millions of bank documents and transactions.

The leak, which was obtained by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF) and French media outlet Mediapart and shared with The Sentry by the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network, showed how the Chinese firms, China Railway Group and Sinohydro, used a middleman with accounts at a bank run by the president’s brother to pump tens of millions of dollars into the pockets of the Kabila family, their associates, and businesses at crucial junctures in what are known as the Sicomines agreements.

When those state-owned construction juggernauts pledged beginning in 2007 to help rebuild and expand infrastructure in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in return for millions of tons of ore, they took a giant gamble.

The multibillion-dollar effort matched President Joseph Kabila’s soaring political ambitions and the nation’s pressing needs for roads, railways, and hospitals, yet its success was far from assured.

But, the Congo Hold-up leak shows that the Chinese state-owned enterprises had a few aces in the hole all along: a shell company, a slick intermediary with a network of companies, and BGFIBank DRC.

The leaked files reveal that the shell company at the center of the scheme—Congo Construction Company (CCC)—received $55 million from foreign sources apparently intended for Kabila and his entourage.

CCC later funneled $10 million back out to safety as the Kabila family faced losing both political power and control over the bank.

These funds transited the international financial system, flowing through major financial institutions like Citibank and Commerzbank to and from a country plagued by corruption, doing so under false pretenses and with little to no documentation, exposing how financial giants whose market values can dwarf the entire Congolese economy fail to protect the world’s poor from kleptocracy.

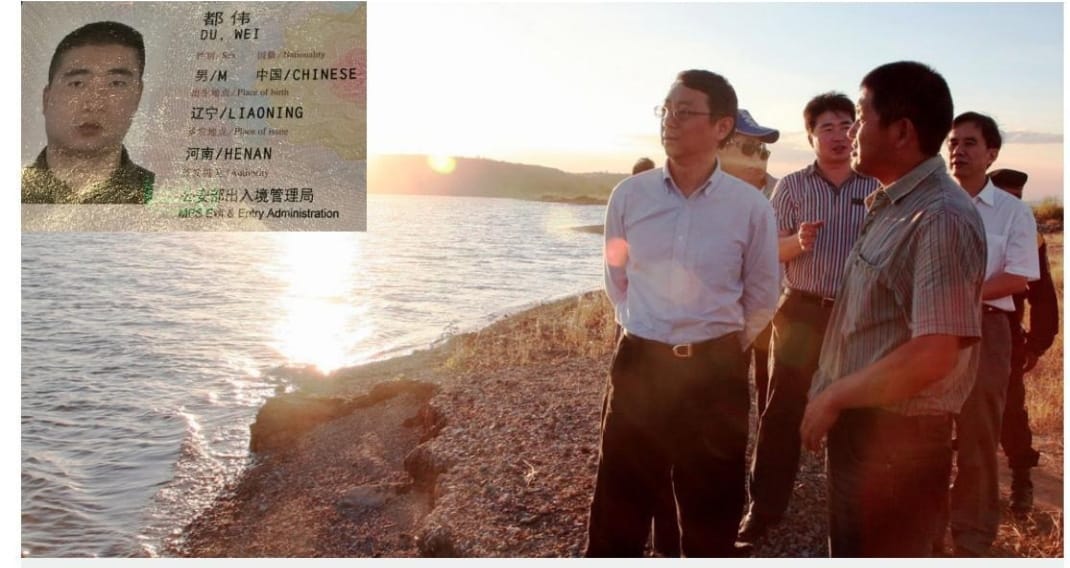

CCC’s owners were a consummate middleman, Chinese scholar and self-proclaimed investment risk expert David Du Wei, and a member of President Felix Tshisekedi’s cabinet, Minister Guy Loando. Du Wei appears to have swung into action in late December 2012, around the time when the Chinese shareholders in Sicomines, a joint venture they created along with the Congolese government to carry out the resources-for-infrastructure bargain, were negotiating with China Exim Bank back to resume financing the project.

That month, he created CCC. From December 2012 to July 2018, Du was one of the most important clients at BGFIBank DRC, where Kabila’s brother, Managing Director Francis Selemani, personally opened CCC’s client account.

CCC helped orchestrate events behind the scenes despite the fact that it engaged in no actual construction and had no legitimate business revenues or expenses on its accounts, BGFIBank DRC records show.

Against this backdrop of financial impropriety, the Kabila-led government repeatedly made decisions that benefited the Chinese stakeholders in Sicomines while the money piled up within the private commercial universe surrounding the president.

According to The Sentry’s analysis, from 2013 to 2018, CCC transferred at least $31 million to companies and people directly linked to Kabila; $21 million, largely in cash, to unknown beneficiaries; $8 million primarily to the Kabila family’s commercial partners; and over $2 million to Du’s own accounts.

CCC paid out the remaining $3 million in transfer fees and to reimburse a loan using funds Cong Maohuai’s toll management company wired Du Wei’s firm. The flow of cash increased as Kabila neared the constitutionally mandated end of his final term in office.

Over the course of one three-month period in 2016, Sicomines wired $25 million to CCC, which then transferred the money to the Kabila family, their proxies, and their commercial partners.

CCC’s role in the Sicomines deal has all the hallmarks of a massive bribery scheme: large amounts of money flowing into the accounts of people with close ties to the president, funds transiting through a bank run by the president’s brother without any meaningful scrutiny, insufficient or inaccurate documentation to justify the transfers, companies with unclear ownership, intermediaries with conflicts of interest, and decisions made in secret with significant financial benefits for the provider of the illicit funds.

This in a deal between state actors in the DRC and China, two countries known to have a high risk of corruption.

This state of affairs is not destiny, however, and nor are tales like this the exclusive province of Chinese corporations or Congolese leaders, a fact proven by the seemingly unending saga of Western oil corruption in Nigeria, for example.

The Backchannel provides a template for holding future leaders, including the DRC’s current administration, to account: Ending this state of affairs will require public vigilance, tenacious investigation and independent local law enforcement to disrupt the circle of actors who connive in looting Africa’s wealth—and hopefully bring the cycle of plunder to a close.

kongopress.com

kongopress.com

kongopress.com

kongopress.com